Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Hollywood

- KP

- Sep 18, 2024

- 5 min read

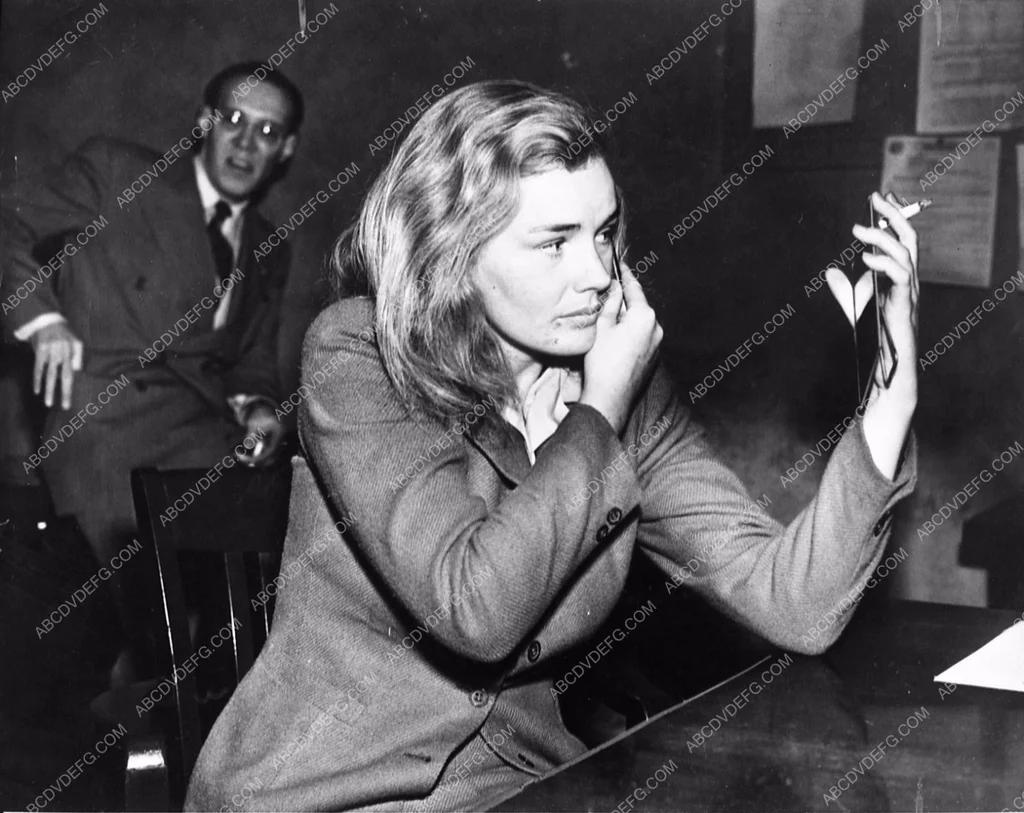

“The Star Who Would Not Go Hollywood,” Frances Farmer ultimately went out kicking and screaming in 1943.

Eight years earlier, the Seattle-born actress signed with Paramount on her 22nd birthday, and in 1936 she shot to fame in Bing Crosby’s Rhythm on the Range. Now a star, studio boss Adolph Zukor demanded she act like one: dress glamorously and get rid of her “disgraceful old jalopy.” But she refused to conform. “From that point on, it seems I made a determined enemy out of him,” Farmer wrote in her memoir Will There Really Be a Morning?.

Her “eccentricities” turned problematic, as depression and alcohol affected Farmer both professionally and personally. She left Hollywood briefly for Broadway, and when she returned, her marriage to actor Leif Erickson was over. He remarried the same day their divorce was finalized in June 1942.

It all reached a boiling point in December 1942 when the actress returned to Los Angeles after a disastrous film shoot in Mexico City to find strangers living in her home. Farmer’s family had moved her belongings into a rented room at the Knickerbocker Hotel in Hollywood, yet when she got there, only a few dresses hung in the closet. “Every personal possession was gone, and I flew apart.”

Farmer, 29, spent the holidays alone, and binge-drinking despite the terms of her probation. Two months earlier in October 1942, the actress had been arrested on a suspected DUI, fined $250, and prohibited from intoxicating liquors for two years. But she couldn’t stop, and when a bartender at the Knickerbocker refused to serve her alcohol, she struck him.

By then, police were already looking for Farmer, who had failed to meet with her probation officer nor pay her fine’s remaining $125 balance. On the evening of January 12, 1943, they knocked on her hotel room door, but she didn’t answer.

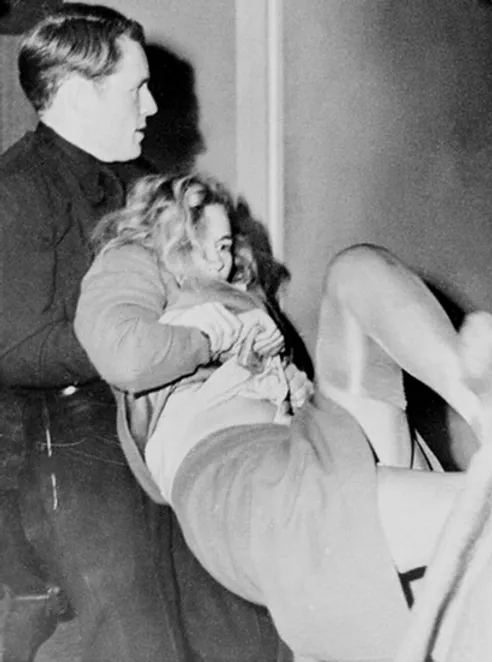

Officers returned the next morning, and forced their way in when the actress opened the door to receive her breakfast. “It’s too early,” she argued. “Come back later.” Farmer, who was nude, dashed for the bathroom and locked herself inside. Police broke down the door and found her hiding behind the shower curtain.

Another fight ensued as they dressed her in a powder blue wool suit. “I was bodily hauled through the lobby, kicking and screaming”—and right past reporters who had been tipped off about her arrest.

At the Santa Monica jail, Farmer was defiant and sarcastic throughout the booking process. What was her occupation? “Prostitute,” she replied.

The next morning, she appeared before Judge Marshall Hickson, who admonished the actress for violating her probation. “Were you fighting at the Hollywood Knickerbocker Tuesday night?” he asked. “Yes,” she admitted, “I was fighting for my country and myself.” Hickson reminded Farmer that she also wasn’t supposed to drink. “What do you expect me to do?” she interrupted. “I get liquor in my orange juice, in my coffee. Must I starve to death to obey your laws?”

Hickson had heard enough: He sentenced Farmer to 180 days in jail. “That’s fine,” she shrugged. But it wasn’t—moments later, Farmer’s request to use the telephone was denied, causing her to fly into a violent rage, knocking over a policewoman in the process. “I did everything I could to destroy the courtroom,” she wrote in her memoir. “It finally took five policemen and a straightjacket to subdue me.”

As she was dragged from the courtroom, Farmer famously cried out, “Have you ever had a broken heart?”

Declared mentally incompetent, Farmer avoided jail time and was transferred to a psychiatric institute with the help of the Screen Actors Guild. Nine months later, her mother Lillian was awarded guardianship and brought Farmer home to Seattle, where she briefly received treatment at Western State Hospital.

In 1945, after Farmer went missing while staying with her aunt in Reno, Nevada, Lillian filed a complaint with the King County Sanity Commission claiming her daughter was “not a safe person to be at large” and must be recommitted. She was, and for the next five years Farmer remained in a high-security ward at Western State.

During that time, the extent of Farmer’s treatment is up for debate. In 1958, she appeared on This Is Your Life and painfully recounted what led to her breakdown and longterm hospitalization. At Western State, “we received shots, or hydrotherapy baths, or electric shock treatment,” she revealed. “This was supposed to relax the tensions and keep us quiet, which it did. I don’t blame the hospital at all—I think that they did everything in their power to take care of the enormous number of people they had, but I really don’t think it helped me much.”

In 1972, two years after Farmer’s death at 56 from esophageal cancer, her memoir Will There Really Be a Morning? was published, and it detailed “unbearable terror”: “I was raped by orderlies, gnawed on by rats, and poisoned by tainted food. I was chained in padded cells, strapped into strait-jackets, and half-drowned in ice baths.”

However, Farmer died before she could finish the book, prompting her late-in-life friend Jeanira Ratcliffe to take over as ghostwriter—and she privately confessed to sensationalizing the memoir in order to have it optioned for a film, with herself as screenwriter. Further proof that Farmer did not fully write Will There Really Be a Morning?: factual errors include the wrong names of her own grandparents.

The 1978 biography Shadowland by William Arnold ignited the accusation that Farmer was given a lobotomy, a rumor that is still widely accepted as fact despite Arnold admitting under oath that it was a fabrication. (For a complete breakdown of Arnold’s countless falsehoods, check out the incredible work of journalist Jeffrey Kauffman)

The discredited Shadowland was originally the source material for the 1982 feature film Frances starring Jessica Lange, but producers reneged during pre-production (Arnold unsuccessfully sued for copyright infringement). The script unfortunately includes much of Arnold’s fiction, however Lange’s portrayal of Farmer is spellbinding—earning her first Academy Award nomination for Best Actress in 1983.

“It devastated me,” Lange admitted, “to be immersed in this state of rage for twelve to fourteen hours a day. It spilled over into other aspects of my life. I was really hell to be around. I took on the characteristic of Frances that was elemental to her demise—battling every little thing that came along.” The sadness of Frances stayed with Lange, who told the New York Times in 1985: “I’ll never do a role like that again.”

Nirvana’s 1993 album In Utero includes the song “Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Seattle,” inspired by her tragic story. Kurt Cobain had read Shadowland years earlier and identified with the Hollywood star’s plight once his own fame skyrocketed as the voice of Generation X. Seven months after releasing In Utero, 27-year-old Cobain killed himself at his Seattle home on April 5, 1994.

Comments